Sammy Maldonado is 15 months older than his brother, David. The age difference is the reason that Sammy may spend the rest of his life in prison for a murder he did not commit, while his brother - the actual perpetrator - is going free.

On 13 August, 1980 - the day that blew the Maldonados' lives apart - Ted Kennedy had just conceded defeat to Jimmy Carter in the Democratic primary for president. Stanley Kubrick's The Shining was terrifying American movie audiences, and the Iranian hostage crisis was sliding into its 10th month.

It was the end of a long, hot summer day, and teenagers David and Sammy decided to escape from their bleak urban surroundings in northern Philadelphia to an idyllic spot called Devil's Pool.

The brothers piled into a friend's 1970 Mustang, stopped off for a gallon of cheap wine, and drove into the park. They hiked down the footpath from the car park until the trees parted

around a rocky outcropping that looked down on a deep, creek-fed basin of water. Swimmers launched themselves from the rocks and into the cold, dark water, drank beers and smoked pot.Before long the Maldonados had befriended another group of teenagers who traded their beer for the brothers' joints. They drank and listened to a kid strumming a guitar, until both boys were drunk, high and feeling bold.

According to court documents, at some point, one of the boys decided "to steal the white kids' box" - a cardboard box they hoped was full of valuables. As the light was fading, Sammy snatched it and took off running. David followed, grabbing a steak knife from the other teenagers' picnic supplies.

The other group gave chase, and Sammy and David got separated from the rest of the group with 19-year-old Steven Monahan hot on their tail. According to the testimony at trial, Sammy almost immediately abandoned the box - which among its treasures held a $10 bill, a report card, and a comb - and Monahan tackled him. David jumped on to Monahan's back and stabbed him twice with the steak knife. Monahan fell, and the brothers took off into the woods.

Back in the parking lot, they flagged down their friends and climbed into the Mustang heading back into the city.

"I think I killed him," David said from the backseat, and started to cry.

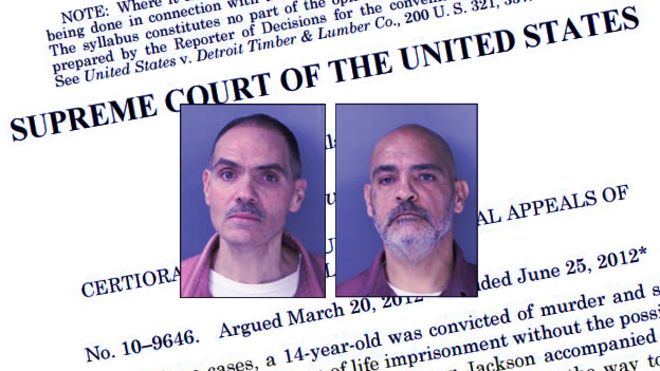

Thirty-seven years later, the Maldonado brothers sit beside each other in the visiting room of the Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution at Graterford in identical faded crimson jumpsuits. They've aged from scrawny teens into middle-aged men. Sammy is the quieter one, with a smooth bald head and professorial glasses. David is taller, lanky with thinning dark hair and a moustache that has turned more salt than pepper. The family resemblance is in the eyes - the same slate grey colour.

After Steven Monahan died - his aorta punctured by one of the stab wounds - both boys were convicted of second-degree felony murder and sentenced to mandatory life in prison without the possibility of parole. Because of the laws on the books in Pennsylvania, the judge in the case had no say on the sentences, even remarking at the time: "I think it's harsh, because I never would have sentenced you to a life term in prison under these facts."

They've spent nearly their entire time in prison in the same facility, Sammy's cell at Graterford is just 15 cells away from David's. Because they're housed on the "honour block", they can visit each other several times a day. Like all brothers they argue and get on each other's nerves, but today there is reason for some levity: in just a few week's time, David is going free.

"I'm elated for him," says Sammy.

David's emotions are more complicated.

"It's bittersweet," says David. "I hate to leave Sam."

They were both supposed to die in prison. But a series of recent US Supreme Court decisions has changed everything for David, who was 17 at the time of the murder, and classified as a juvenile.

In the 2012 case of Miller v Alabama, the high court decided mandatory life sentences for juveniles constitute a violation of the US constitution's eighth amendment, which bars cruel and unusual punishment.

Four years later, the justices ruled that the Miller decision should be retroactive, meaning the roughly 2,300 men and women across the US who'd been sentenced to life in prison as children had a right to be resentenced, and therefore eligible for parole and release.

"Because juveniles have diminished culpability and greater prospects for reform… they are less deserving of the most severe punishments," Justice Elena Kagan wrote in the Miller decision.

"Our decisions rested not only on common sense - on what 'any parent knows' - but on science and social science as well."Both Sammy and David say that in their first few years in prison, they were terrors - drugs were easy to obtain and they graduated from smoking weed to shooting heroin. They fought other inmates, and coped with their fates by spending as much time as possible in an intoxicated stupor.

But by their early 20s, they'd both lost interest in drugs. Sammy took up boxing, as evidenced by a few missing teeth, and eventually became a born-again Christian. David started going to classes and earned his GED (a certificate equivalent to a high school diploma).

"I had to start doing the time instead of letting it do me," he says.

By the time of his release, David had earned a masters of theology and was working as a drug and alcohol counsellor for Spanish-speaking inmates. Sammy - who says he spends most of his time alone in his cell studying the law and the Bible - has a job as a teacher's aid for inmates working towards their GEDs.

"I'll be 54 next month, he just turned 55," says David. "We're not the kids we were. We don't have the problems we had back then."

There's at least one court case making its way through the system that could result in a similar game-changing decision for people like Sammy.

Ted Koch is a lawyer representing Luis Noel Cruz, an inmate in Connecticut who committed a murder on the orders of the Latin Kings gang when he was 18 and a half years old. A federal judge has agreed to hear arguments this fall that the Miller decision should apply to someone who was just past his 18th birthday.

"It's arbitrary - the science doesn't draw bright lines, so the law shouldn't either," says Koch.

No comments:

Post a Comment